Most investors make rational decisions, though not necessarily correct or optimal. A person’s biases, lack of perspective, lack of knowledge, fear, confidence levels, not to mention their liquidity needs or spending habits, can all cause suboptimal investment choices. For most decisions we make as human beings, we are fighting against our innate survival biases and emotions. An inexperienced investor can fall prey to natural human instincts that are designed to keep a person safe. But, many of these natural human instincts are the enemy of optimal investing.

Behavioral and cognitive biases are programmed into our consciousness for one simple reason: the world is too complex for us to process all of it. Our brains put rules in place to allow us to ignore vast amounts of what we experience so we can devote our highest attention and cognitive power to the things that pose the biggest threats to our survival. In terms of keeping us alive, these biases are quite effective. In terms of making optimal investment decisions, they are purely obstructive. The key to making good investment decisions is to understand your personal and behavioral biases and put a process in place to protect yourself from them.

Here is a sample mechanism to put this recommendation into practice. Imagine a stock you own halves in value. You can evaluate the loss with two unique perspectives:

1)Instinctual, Emotional Response: the emotion of losing 50% in a stock can overwhelm any rational thought of whether it is a good stock to own or buy at this price. We call responses like these “taking a spin on the Wheel of Cognitive Misfortune”.

-

Recency bias: “This thing only goes down. SELL.”

-

Confabulation: “I knew buying this stock was a bad idea. SELL.”

-

Pareidolia: “This is just like when I bought GME at $350. Same thing is going to happen here. SELL.”

-

Negativity Bias: The part we didn’t mention was that prior to this 50% sell-off, there was a 300% gain.

-

Just-world bias: “I cheated on my taxes; I deserve this. Please stop the pain. SELL.”

These emotions can be further exacerbated if you bought more than you should for your portfolio size or if it was purchased on margin. There are many other emotions and biases that can come into play, but these 5 are examples of thoughts that gnaw on your brain and none of them are useful reactions or approaches to investing . Instead, you should be thinking and analyzing, which leads us to option two.

2)Analytical Perspective: whether you should sell out of your position or buy more is entirely dependent on the specific context. It’s unlikely you can determine the right answer with certainty, but evaluating the details can get you a lot closer than your emotions and biases.

- If it was massively overvalued and all that changed is investor psychology, it might be time to buy more. Unfortunately, even if this is the case, it still might go down a lot more before it goes back up.

- If it went down because earning expectations were lowered, the selloff could have been either an overreaction or an underreaction to the news. So, it still depends.

- If the stock market overall went down due to the normal cycles of investing, it might actually just be cheaper and best to hold onto.

This example of emotions affecting investment decisions is just one experience that a novice investor will struggle to overcome. It’s also an illustration of why beating the market as a stock picker is difficult and futile for most investors.

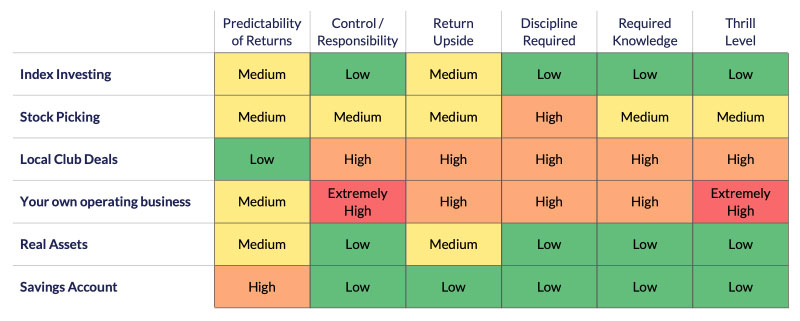

There are five Core components that Individuals utilize to manage their assets:

- Index investing: broad indices are available for all of the major asset classes in an investment portfolio. These indices are very hard to beat in terms of performance and impossible to beat in terms of fees. This is the easiest and most straightforward option.

- “Stock picking”: Picking stocks and bonds and varying exposure over time. Though indices are hard to beat, this makes sense for a lot of individual investors as it can be very educational, profitable. Not too mention, it gives you a hobby. However, you probably won’t beat the market and adding too much turnover will likely greatly degrade after tax results.

- Local club deals: This can work for disciplined investors with a decent network of like-minded peers. This style keeps an investor close to his investments and meets the needs of an investor who needs to be in control.

- Your own operating business: If you know the business well and work at it full time, this will likely yield the highest return on your capital. This is not a sustainable strategy as the cash flow outstrips the cash needs of the business.

- Real assets: the equity you have in your home should be considered part of your investment portfolio, especially when inflation is a serious risk.

- Savings accounts: This strategy is “safe” as it relates to your nominal asset but has no chance to keep pace with inflation and cover growing cash needs.

All six of these options can reasonably serve as a component of an overall portfolio, and they all map onto the asset classes in institutional portfolios. Which you choose is highly dependent on who you are, your risk tolerance, your liquidity and spending needs, your discipline level, your knowledge level, your need for control, and your need to “be in the game”.

Deciding the optimal mix of these components is fairly subjective to the individual. What is not subjective, however, is the optimal method by which such decisions will be made. All investors should have some form of rudimentary Investment Policy Statement (IPS) that guides their investment decisions. The underlying purpose of guiding your investment decisions with an IPS is to protect your assets from your cognitive and behavioral biases. The IPS specifies high-level goals and objectives, expected returns and volatility, target asset allocation, risk tolerance, liquidity requirements, trading constraints, bands for rebalancing, and other, more sophisticated constraints depending on the expertise of the investor.

All institutional investors implement an IPS, and doing so as an individual investor will allow you to become more like an institution. Admittedly, institutional investors retain some advantages over individuals, even those with an IPS. Namely, they have far greater resources and access to financial instruments based on their size that individuals do not. Having said that, institutional investors also retain some disadvantages. The greater size of an institution often causes their teams to be incredibly slow moving. Also, there are collective institutional personalities created by the structure and ability of their investment teams and governance boards, which can lead to group think and competing opinions can muddy the objective function. Too often the unstated objective function becomes, “do not take any chances or make any investments your peers don’t and do not vary your allocations from industry norms.” Individual investors undoubtedly have limitations relative to institutions, but that does not mean they are doomed to lower returns. For the last several years in fact, Ivy League endowments have underperformed a basic 60-40 portfolio.

Whether you are an individual or institutional investor, an effective investment process requires the characteristics in the list below. This list is the bare bones of an investment strategy. Even if you choose a very simple liquid strategy of varying your exposure to Equity and Fixed Income ETF’s, its important to keep the discipline espoused below. We have built an entire suite of tools and whitepapers to expand beyond this. Individual investors can invest more like professional investors utilizing our tools. We break the process into a few distinct phases and have the guidelines and tools to work through the process.

-

An IPS with a clearly stated objective function and a broad set of investment guidelines. The most important part of the IPS is your asset allocation scheme. Our NEMO (New Endowment Model) whitepaper and tool provide a framework for determining the optimal asset allocation scheme given the details of your financial status and your preferences.

-

An implementation plan that realistically incorporates what you have access to. NEMO is the best place to start building, but the constraints you face will dictate what you can invest in. For instance, do you have access to liquid alternative, real estate or private equity managers? Do you have access to or are you comfortable with futures? For an institution or expert investor, answers to these questions will be readily known, but most investors have way too much going on in their careers and families to take on all the responsibility of managing their assets, which is why they outsource to a wealth manager. For these investors, picking an RIA is a crucial step; our piece How to Evaluate and Select an RIA gives a guide to that decision.

-

On top of a basic asset allocation scheme, you need a deep understanding of what real diversification looks like. This involves having the ability to model your asset allocation across different regimes and an understanding of the joint distributions of the investments in your portfolio. For example, how will Bonds perform vs. Stocks in different investment regimes. Our SOCIO (Systematic Outsourced Chief Investment Officer) whitepaper and tool allow a user to model portfolio options to see what they can expect from their desired portfolio structure.

-

Knowledge of the future range of potential outcomes that each of your investments have. In addition to the hindsight of understanding how different investments have behaved in the past, investment teams need to understand how current market conditions will impact their portfolios on a continuous, ongoing basis. We have two methods that arm investors with this ability. Ravel gives a view of current economic reads on global economic Growth, the attractiveness of the Yield associated with global equities and fixed income, an assessment of current Risk Appetite / Fear in the market, and current Inflation expectations. Investors can use this report to understand how attractive the current environment is for their investment mix on an ongoing basis. Secondly, Bear Tracker provides a continuous systematic analysis on the factors that impact the US equity market.

-

A consistent risk assessment process. Ongoing risk management involves two sub-components:

A framework where all investments can be cross-referenced for coherent evaluation on a regular basis. Technology is crucial for doing this efficiently; Qubit is our proprietary platform for doing just that.

A mechanism for assessing historical decisions. Even an expert investment committee with effective self-discipline will make decisions that require course correction. If systematic strategies are part of your portfolio, we have a piece to assess them: A Guide to Understanding Systematic Investing.

Embedding these components in your portfolio upon initial setup rather than adding them on the fly when problems arise will make them much more efficient and objective. Our What is Risk? paper explains how we, as a systematic investor, think about risk and will help you understand the technical details of effective portfolio risk management.

-

A vigilant ongoing assessment of fees and taxes paid. Unfortunately, investors have to be constantly on guard to make sure their returns are not eroded by investment fees. That does not mean we think fees are uniformly unwarranted; there are straightforwardly definable components that warrant paying fees, which can be explored in our **Fee-Fi-Fo-Fum **tool. As far as taxes goes, it’s a simple optimization to pay as little as possible; incorporating a tax expert is usually necessary.

Our core message is that an investor needs to determine who he is and what he values. Choosing an investment strategy that fits you should be accompanied by an investment process that reduces the risk of your “rational” decisions being BAD decisions. A strong process should rarely require phrases like “now that I think about it” to explain your reaction to a decision you made. Think about it thoroughly from the start and set yourself up for success.